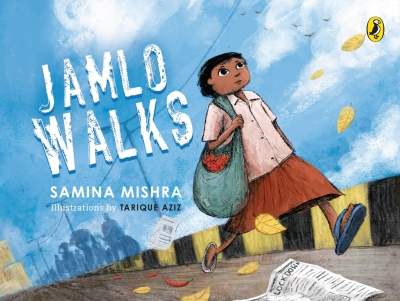

New Delhi (IANS) She says ideas are mysterious things. They come to us in many different ways and then we begin to make choices and make decisions about what we want to do with them, and shape the work. Delhi-based writer, filmmaker and teacher Samina Mishra wrote the first draft of the ‘Jamlo Walks’ (Penguin), to be released on April 19, in one sitting. A picture book for ages 7-9, but a story that she hopes children across ages will read.

A book on what the lockdown did to the people, particularly its young citizen, Mishra, who wrote the book, which has illustrations by Tarique Aziz, in April last year still remembers those videos of the migrants walking through the night, out of Delhi, on the Yamuna bridge “That was such a searing image. And it was juxtaposed by the middle class apathy all around, from what people were saying on social media about the migrant labour walking, to stories about how domestic workers were being treated at colony gates and incidents of police walking into bastis and thrashing people for being outside etc. It was all so horrible � as if our humanity had completely disappeared. The working class has always been treated differently but this � it was as if they were not people. And then when Jamlo’s story was reported in the media, it was simply heartbreaking. Considering I work with children and the experiences of childhood, I thought of what this divide means for all children, how are they to think about these stark differences across different childhoods, would they go on to continue institutionalising this inhumanity… So, I think the first draft just came out of a need to respond to all this,” she tells IANS.

Considering the book was quite ‘visual’, the idea of it being a picture book developed. Though she wanted to, doing anything longer would not have been possible for Mishra without actually getting out on the ground. “That’s my process as I work with documentary film. And I couldn’t get out at that time. So it remained a short story that I kept working on,” says the writer of ‘Hina in the Old City’.

In fact, when Lockdown 1.0 was announced, she began an online art project with kids, ‘The Lockdown Art Project’, asking them to reflect on their experiences of the lockdown. Stressing that it is important to include children’s voices in all that we grapple with in the world, and making room for them to express themselves is part of her practice, she adds, “These were all middle-class children and the enormity of the gulf between those who had access to the Internet and those who didn’t was glaring � everything that was present from before just became worse and more solidified. There was all this content for children being shared generously online but so many kids who couldn’t access it. Old media suddenly became important and so I recorded a set of audio stories for Radio Mewat � just to create content for kids who could not access content on the internet.”

For Mishra, writing, making films and teaching feed into each other and complete her. “For me, they all inter-connected for me. My creative practice involves using image, sound and text to tell stories or share experiences of a particular time and place. The challenge of practice across both film and writing is the same in many ways � how to create something that engages both the heart and the mind.”

Adding that teaching creates a context for her to engage with the world, with children and young people, the author, who that in both formal and non-formal spaces, says, “Whether I am teaching the IB Film programme or doing writing workshops, I am engaging with the idea of the arts in education, and that connects to the idea of making work that engages the heart and the mind. I have to be able to connect with the young people I teach and so I learn a lot from that process that I think shapes my personal creative work.”

Mishra, who has just completed her latest film ‘Happiness Class’, which is about the Happiness Curriculum in the Delhi government schools and has been made for the Foundation for Universal Responsibility as part of the Dalai Lama’s particular interest on social and emotional learning in schools, says, “It explores the possibilities and the challenges of implementing such a curriculum in the larger context of inequality, stress and conflict in the world through the children and their families, and the teachers in three schools.”

“The film is ready and we hope to have an online event later this month. Physical screenings seem unlikely in the immediate future but I really hope this will change soon,” says the filmmaker who has made films including ‘The Teacher and The World’ (2016), ‘Jagriti Yatra’ (2013), ‘Two Lives’ (2007), ‘The House on Gulmohar Avenue’ (2005) and ‘Stories of Girlhood’ (2001).

Talk to her about her active social media handles during the CAA-NRC protests in Delhi and she says though an erratic social media user, she does post a lot when in the midst of something. “It’s part of that idea of creative practice as a sharing of the experience of time and place. The anti-CAA protests began in my immediate neighbourhood, so they found their way into my social media. And yes, because I was surrounded by so many who couldn’t see the harm that the CAA-NRC would do to our lives � and I mean all lives, not just those who tit would target � my posts became a way of talking about that harm and how the coming together of people across class, caste, religion, gender was such an empowering and hopeful feeling.”

Feeling that media � mainstream or social � must create space for diverse voices and varied experiences, she adds, “So, dissent is or should be embedded in that. But it (dissent) can be expressed in diverse ways too. One way is to speak directly � and often that is what is targeted by censorship. But there can be other ways that communicate dissent by focussing on the form of what is shared and not just the content. I think social media often provides room for multiple forms when mainstream media does not. I think it is easier to control mainstream media. Social media is more unruly, less controllable � which is not to say that there are no issues of control and power dynamics with social media, just that they operate differently.”

Pleased that the children’s literature space in India is much more bigger and varied now, she feels there’s still a long way to go and we have to see how the pandemic impacts the sustained creation of new work. “However, in terms of the kinds of stories being published, the quality of artwork and production, we have come far ahead of what it was like when I published my first children’s book in 2000. However, there is little room in the media for disseminating that � for example, most children’s books are reviewed online by a growing community of kidlit lovers but in the mainstream spaces, children’s literature is still seen as something lesser-than ‘real’ literature.”

For someone who has done extensive work with Muslim children in Okhla’s slums, she feels there is a need for more project after the recent Delhi riots and CAA agitations.

“Okhla is a diverse space and I have mostly worked with middle-class kids. My book, ‘My Sweet Home’, came out of a workshop I did with children in the Jamia school � these are not kids from working class families living in slums, although many neighbourhoods in Okhla that they lived in are riddled with infrastructural issues similar to slums. Some of those children from that workshop are now studying in Jamia, some of them have created artwork during the anti-CAA protests. There is always a need for doing projects with children that involve art because art opens up ways of self-expression, of looking at the world in ways that can create dialogue � when do we not need that!”

Talking about her forthcoming ‘Nida Finds a Way’, a chapter book for young readers, part of Duckbill’s Hole series, she recalls that it began with a conversation with Sayoni Basu about the lack of representation of Muslim children in Indian children’s literature. “This is changing thankfully but we can still do with more diverse stories. I think we need stories where there are Muslim characters but it’s not that which is necessarily the focus of the story. So I started writing about Nida who is growing up in Okhla – just a curious, adventurous 7-year old with an overprotective father who she loves a lot but has to find a way of getting around to do what she wants. The story is about how she does that in her everyday, and also how she does that when her everyday begins to include the Shaheen Bagh protest.”