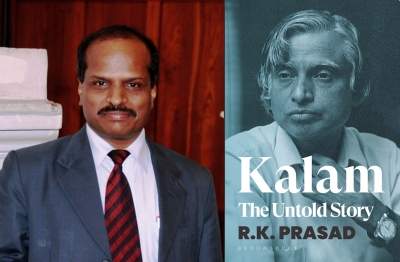

Role model, icon, space scientist, missile man, bestselling author – but in the small exclusive world of New Delhi’s power centres, all that can count for little with the bureaucrats who set the rules and the politicians to whom they report. In ‘Kalam: The Untold Story’ (Bloomsbury), R.K. Prasad, his private secretary from 1993 to his death in 2015, shows us another Kalam – accomplished, successful, always modest despite the high positions he occupied, as also vulnerable and innocent.

Some excerpts:

Among those who were not in favour of Kalam was the Congress chief. It was believed that Kalam did not discourage questions that were raised about her (Sonia Gandhi’s) Indian citizenship after she emerged victorious in the 2004 elections and the Congress wanted her to become prime minister. In his memoirs Kalam has written that he received a large amount of correspondence from both individuals and institutions questioning her citizenship status and that he had passed them on to the relevant agencies.

In ‘Turning Points: A Journey through Challenges’, Kalam wrote: During this time, there were many political leaders who came to meet me to request me not to succumb to any pressure and appoint Sonia Gandhi as the Prime Minister, a request that would not have been constitutionally tenable. If she had made any claim for herself I would have had no option but to appoint her.

It does appear that Kalam was not a walkover and wanted due process to be followed but the Congress leader considered this as his doubting her credentials to become prime minister (whether she wanted to or not). Kalam never said anything openly about her citizenship, but somehow I got the impression that everything about what he did and did not do at the time indicated that he felt she could not become prime minister. That must have been relayed to her or was sensed by her.

There was another episode that alienated him from the Congress chief even more. In 2006 the government moved an ordinance to redefine ‘office of profit’. Kalam returned the Office of Profit Bill which exempted certain offices of state and central governments – including the National Advisory Council (NAC) headed by Sonia Gandhi – from the purview of office of profit for MPs, but when the UPA sent it back unchanged, he signed it.

As an MP, the Congress chief could not hold any office of profit. So this ordinance was widely perceived as a move to save her from disqualification as an MP. A mighty furore erupted, and many political parties – the BJP and the Samajwadi Party in the forefront – petitioned the President for her disqualification as an MP.

Kalam’s attitude towards whatever files the government sent him was to keep them and examine them. He would not just mechanically sign them and send them on. An MP could hold only one post in the government. The Congress chief was UPA chairperson and NAC chairman. As per the rule, she could not hold so many posts. She had to resign either as MP or as NAC head. It was because of Kalam’s adamancy that the ordinance was put on hold.

The Congress chief responded by dramatically resigning as both MP and NAC chief, and for some time she was not an MP till she got re-elected. That she felt Kalam did not take her side was evident when Rahul Gandhi came to meet Kalam. He was closeted with the President for a full hour. That was the only time I saw Rahul Gandhi meeting Kalam. The next time I saw him was at Kalam’s funeral in Rameswaram, travelling in a special aircraft all alone nine years later to show the nation that they were not against Kalam.

To go back to the meeting, once Rahul Gandhi left the room, I asked Kalam, ‘Sir, why has he suddenly come?’ Kalam gave me some ridiculous explanation, but was smiling broadly. ‘He wanted my guidance,’ was all he told me. Definitely, there had been some tough talk behind those closed doors that day.

It is to Kalam’s credit that despite these run-ins with the Congress chief, he was gracious enough to extend help to the Congress and lent a hand in preventing the fall of UPA-I. The government was in a critical condition and was seeking a vote of confidence over the India-US nuclear treaty, the seeds of which had been sown in 2005 between then the US President George Bush and then Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh.

The left would clearly not vote for it, having ideological problems with the deal. But Mulayam Singh Yadav, the Samajwadi Party chief, whose support was critical for the government, was not entirely convinced about the deal either. Finally, Mulayam agreed that if Kalam said the deal was good for India, he would support the government. Kalam was no longer President and had moved to a house he had been provided on Rajaji Marg.

Mulayam visited him there and discussed the deal with him. Kalam told him the deal would be good for India and that the country should proceed with it. When Mulayam emerged from the meeting, he had decided to support the deal, and the government survived.

Still, the Congress chief neither visited nor called on Kalam to acknowledge the good turn he had done her government. Of course, to be fair to her, she had never requested him to speak in support of the deal either. But then, Manmohan Singh soon visited him at his house to personally thank him, perhaps on his chief ‘s instructions.

(When and why Manmohan Singh didn’t keep his word)

In 2011, when the nation was reeling under various corruption scandals that were being reported every other day – the Commonwealth Games scandal and the 2G and coal ‘scams’ – Kalam was disturbed at the developments and asked us to connect him to Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. Within no time the prime minister called back. Kalam told the prime minister he wanted to discuss some issues of national importance with him at his place. Manmohan Singh immediately responded with a ‘Yes, of course’. But instead of Kalam visiting his office, he would come over to Kalam’s residence, he assured him.

Kalam was happy that the prime minister had responded positively to his request. But the visit was not to be. Manmohan Singh never made it, despite several reminders sent to his office. We were told later he allegedly could not get the approval of his leader for the meeting. This happened again the next year. I must have spent a whole day making those telephone calls to Singh’s office. The prime minister was simply not permitted to meet Kalam. A meeting would of course have set the rumour mills ringing. There would be speculations on the meeting, and a press statement or conference may have had to be held to clarify what the meeting was about. There would have been ramifications.